Web3 Infra Series | The Surveillance State Comes to Britain | Why

Centralized Digital ID Is the Wrong Answer

Published on Oct 13, 2025

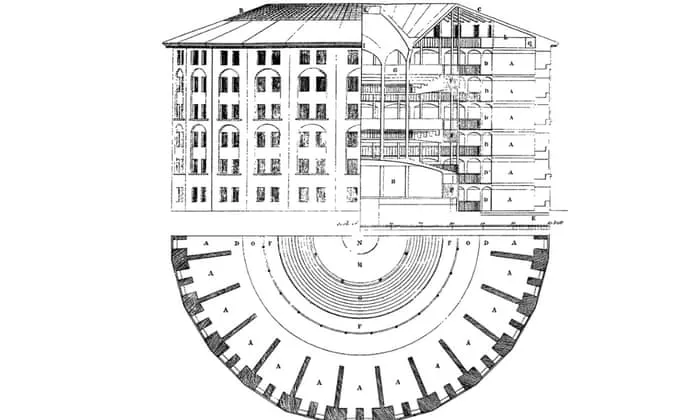

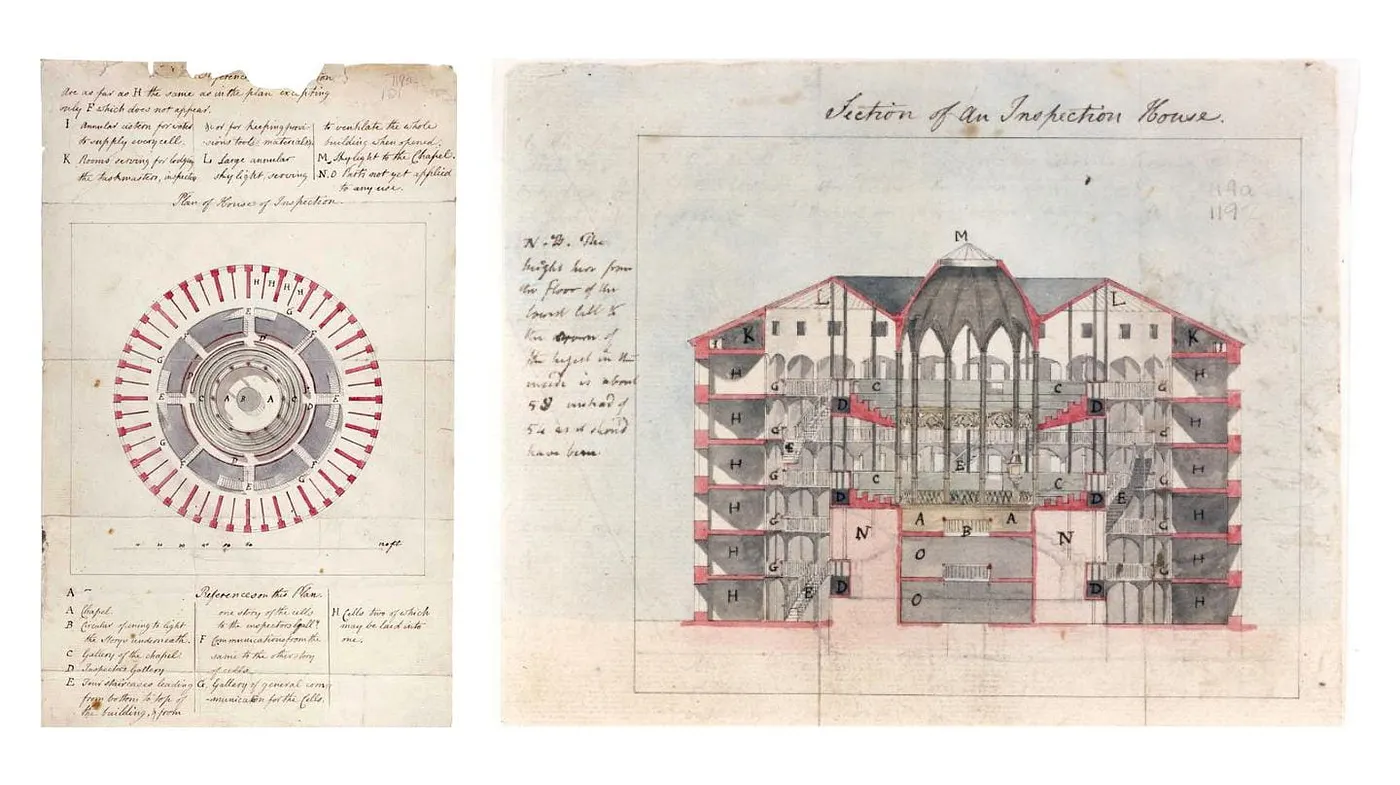

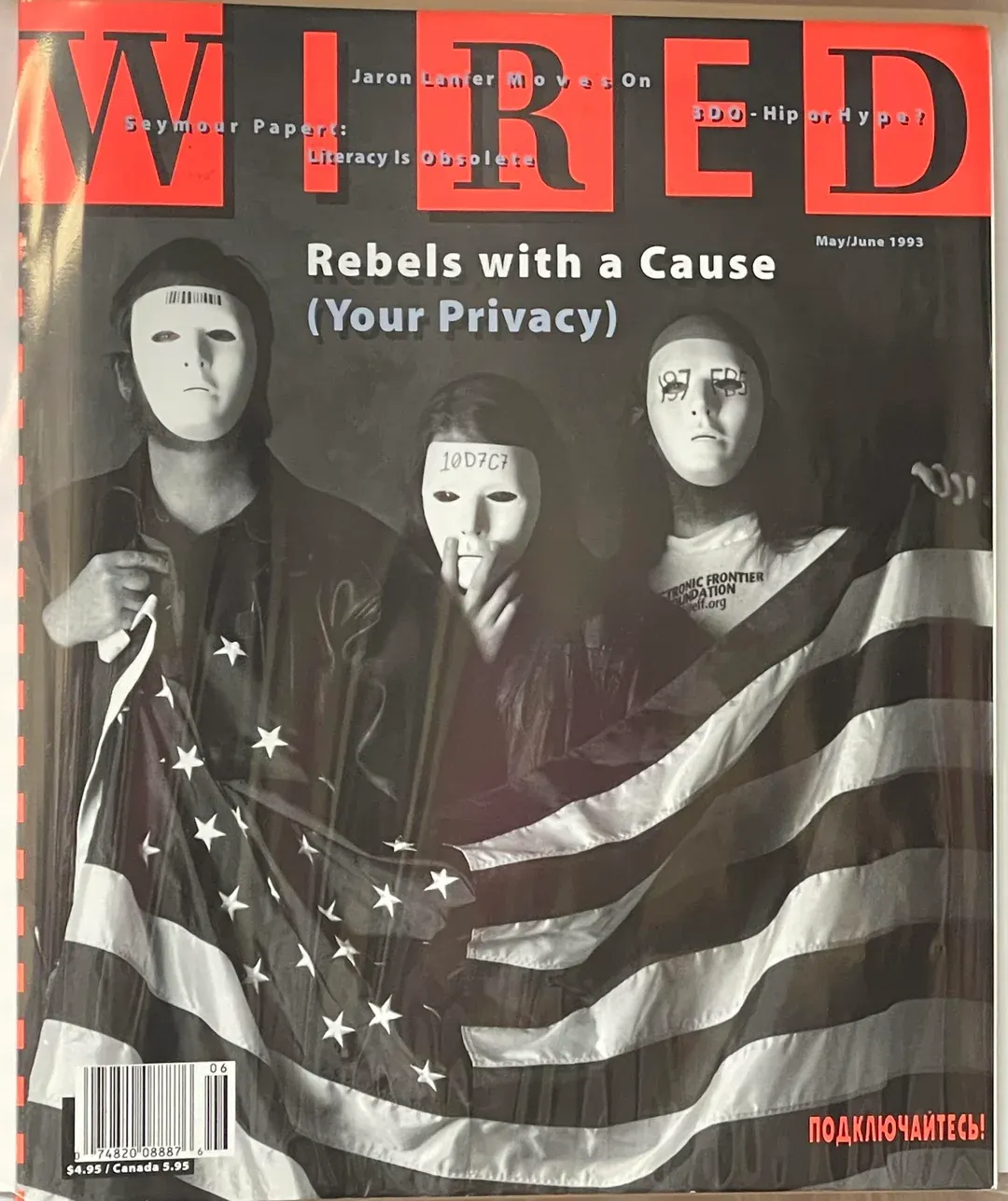

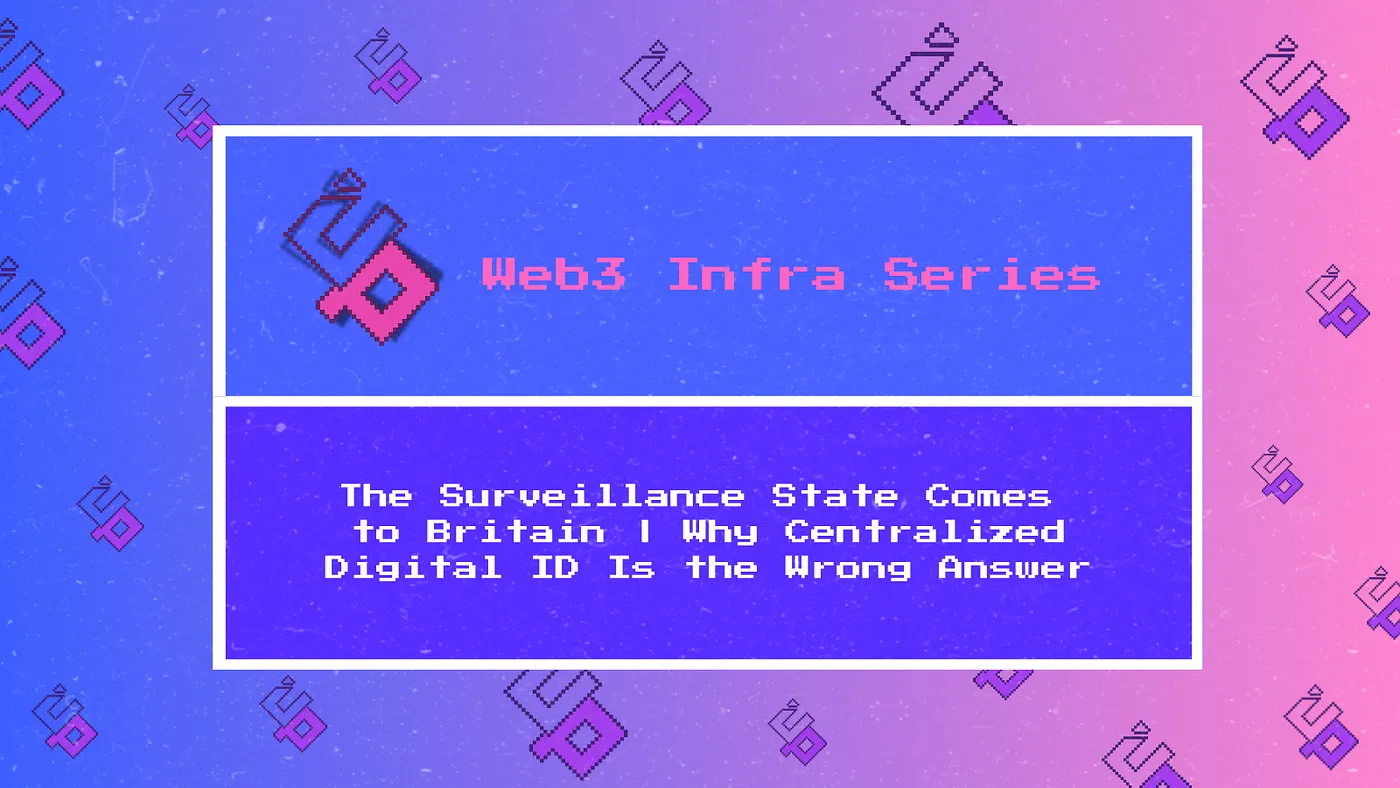

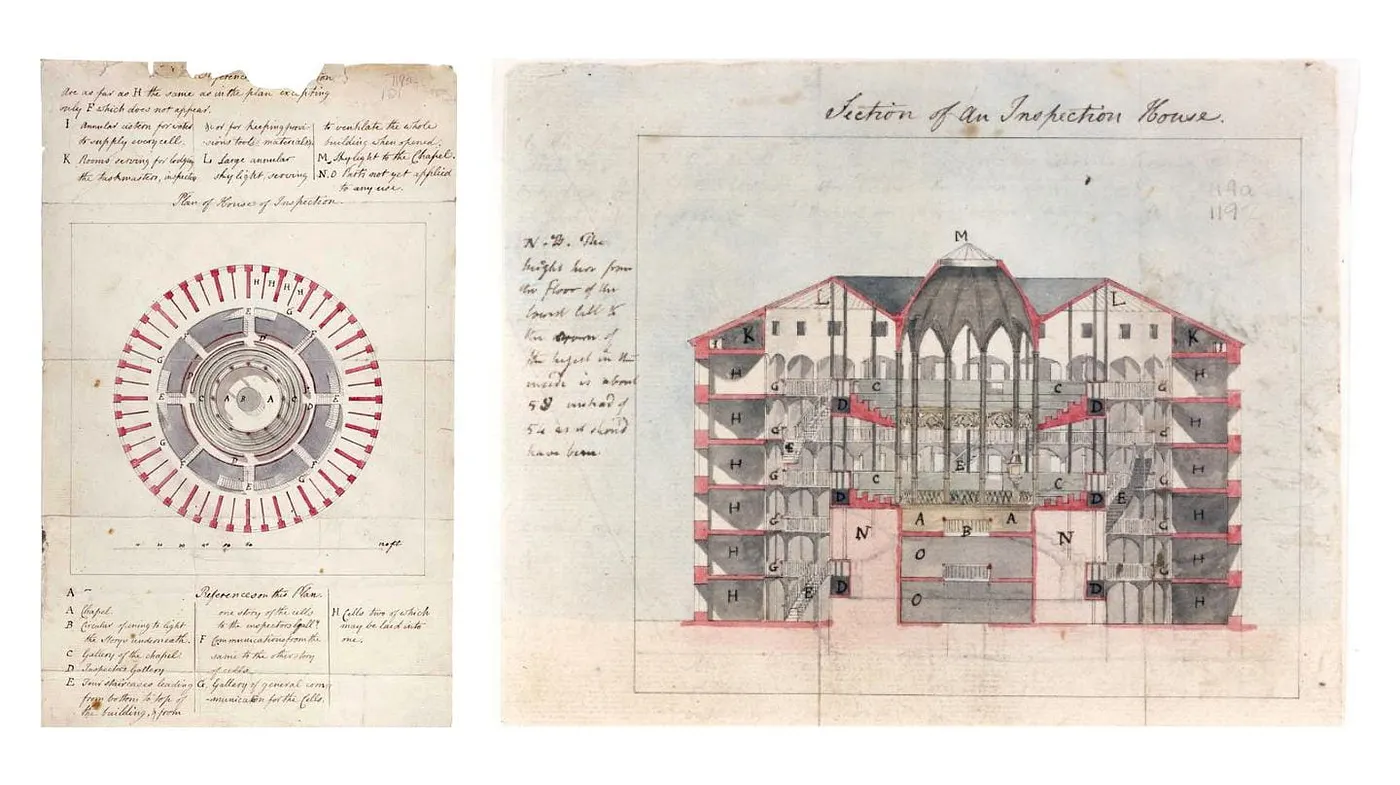

In 1785, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham designed the perfect

prison, the panopticon as he called it, featuring a central watchtower

surrounded by cells arranged in a circle that allowed a single guard

to observe every prisoner without them knowing whether they were being

watched. The psychological effect was profound, with inmates modifying

their behavior constantly and assuming surveillance even when none

existed, creating a state of perpetual self-monitoring that achieved

control through the mere possibility of observation.

Today, 240 years later, Britain is building Bentham’s panopticon on a

national scale through Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s announcement of

mandatory digital ID cards, signaling a fundamental shift in how

citizens relate to their government as they trade hard-won privacy

rights for the false promise of convenience. The timing reveals

everything about political opportunism disguised as progress, as

governments worldwide seize moments of crisis to normalize

comprehensive population monitoring and populist pressure over

immigration provides convenient cover for surveillance infrastructure

that extends far beyond its stated purpose.

The UK scheme, scheduled for implementation by 2029, requires all

citizens and legal residents to maintain smartphone-based digital

identities for employment verification, and though officials promise

these IDs won’t need daily carrying, the infrastructure being built

creates the backbone for something far more invasive than immigration

control. History teaches us that surveillance systems, once

established, never remain voluntarily limited in scope, evolving

instead into comprehensive tools of social control that would shock

their initial proponents.

The government’s sales pitch echoes familiar themes from authoritarian

regimes, offering promises of efficiency, security, and modernization

that make digital IDs seem like inevitable progress rather than a

potential overreach. If we cast our minds back to East Germany, the

Stasi turned citizen identification into a mechanism of pervasive

surveillance, tracking daily lives and controlling movement under the

guise of administrative necessity. Today, countries like Estonia,

Denmark, and Australia are cited as successful examples where digital

identity systems bring practical benefits, constructing a narrative of

technological advancement that masks deeper concerns around power and

control.

This framing paints surveillance infrastructure as mere administrative

convenience, glossing over the reality of unprecedented government

oversight.

If we scratch beneath this veneer of administrative efficiency, then a

much more troubling picture emerges, as these systems evolve with

frightening speed from limited-purpose tools into comprehensively

sinister surveillance infrastructure where today’s employment

verification becomes tomorrow’s access control for healthcare,

banking, transportation, and eventually every aspect of civic life.

The technical architecture reveals the true ambition, with centralized

digital identity systems creating comprehensive profiles that track

movements, transactions, relationships, and behaviors in real-time as

every verification request becomes a data point in vast government

databases building detailed maps of citizen activity.

Privacy advocates from Amnesty International UK warn that such systems

create “huge risks for identity theft and a honeypot for hackers and

online criminals,” but the cybersecurity risks absolutely pale beside

the political ones that emerge when governments accumulate

comprehensive digital dossiers on their populations. The temptation to

expand surveillance powers becomes irresistible once the

infrastructure exists, transforming what began as administrative

convenience into tools for social and political control that

fundamentally alter the relationship between individual autonomy and

state power.

Bentham’s panopticon was never actually built in his lifetime, but its

psychological principles have haunted prison design ever since, with

the genius lying in behavioral modification rather than architectural

innovation. The Victorian workhouses in 19th-century England

incorporated similar surveillance mechanisms, using strict observation

and movement controls to regulate the poor under the guise of

institutional care. When people believe they might be watched, they

police themselves, creating a system of control that operates through

the simple possibility of surveillance rather than its constant

presence.

Modern Britain is constructing a technological panopticon where

citizens know their every digital interaction might be monitored and

recorded, fundamentally altering how individual autonomy relates to

state power in ways that would have horrified even the architects of

liberal democracy.

The exclusion effects compound these surveillance concerns, as Amnesty

notes that “many older people will not have a smart phone or be able

to register properly” and “some people may have problems accessing

services”, creating systematic discrimination where technological

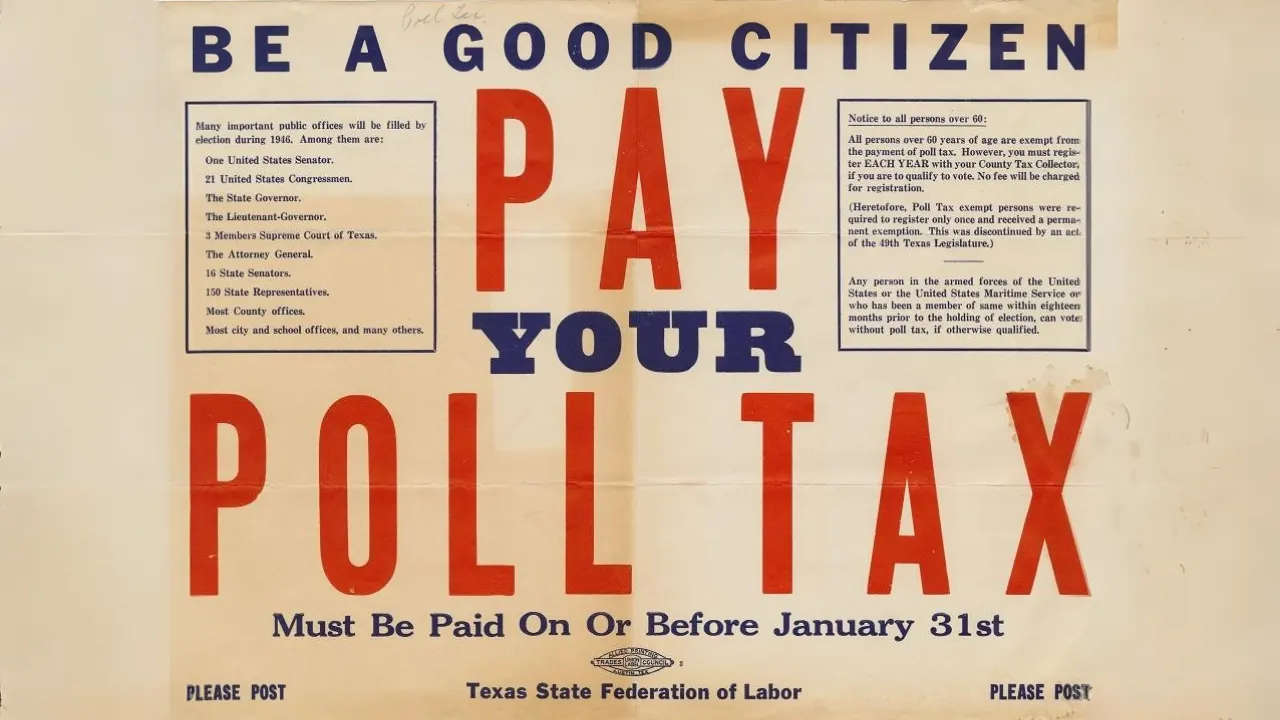

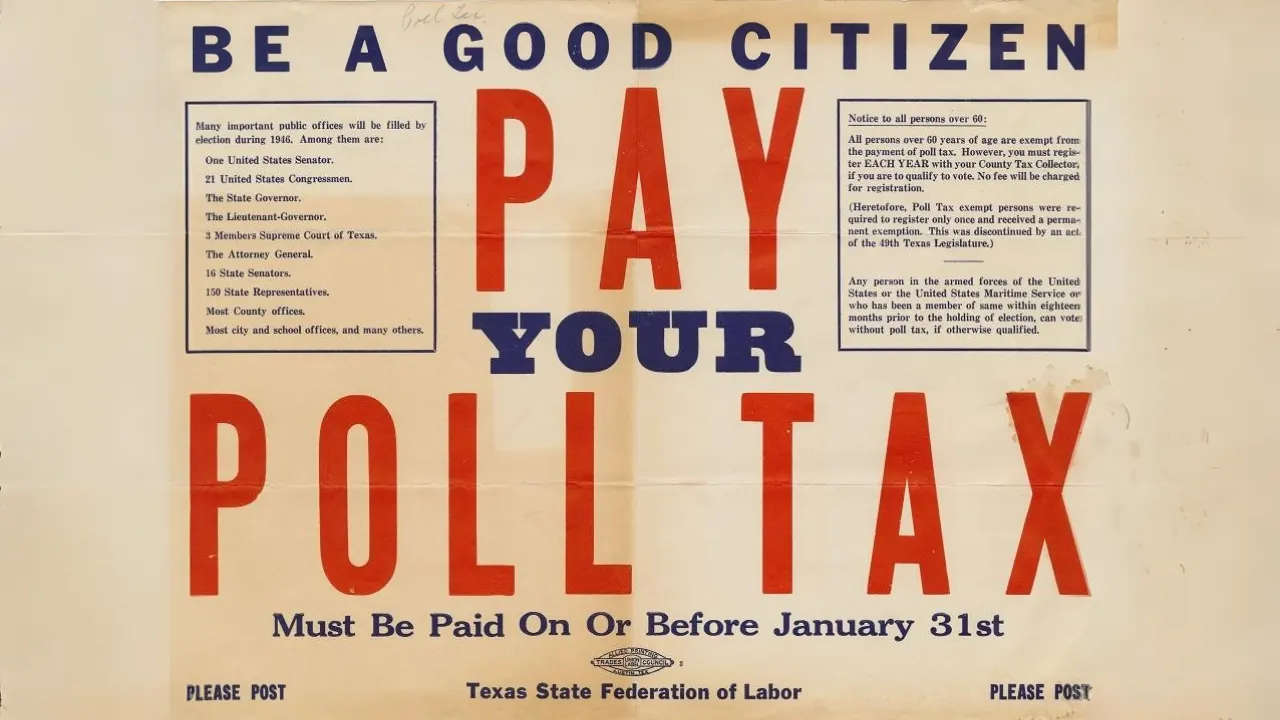

compliance becomes a prerequisite for full citizenship. Historically,

similar bureaucratic barriers like Jim Crow-era poll taxes and South

Africa’s pass laws used documentation requirements to disenfranchise

and segregate communities, showing how identity enforcement can become

a tool for social exclusion.

This effectively divides society into those who can navigate

government-mandated systems and those who cannot, establishing a

two-tier citizenship where basic rights depend on technological

literacy and smartphone ownership rather than legal status or

democratic participation.

Imagine what happens when basic rights like employment depend on

maintaining valid digital credentials, as governments gain

unprecedented power over individual behavior and citizens who dissent

from policies, participate in protests, or engage in political

opposition could find their digital identity privileges restricted or

revoked entirely. The infrastructure for economic exile becomes as

simple as updating a database entry, creating a system where political

conformity becomes necessary for economic survival and dissent carries

the ultimate penalty of digital exclusion from society.

In 1970, computer scientist James Martin wrote about the “fishbowl

effect” of centralized data systems, observing that the larger and

more valuable the data repository becomes, the more attractive it

appears to attackers who can focus their efforts on high-value targets

rather than scattered, smaller databases. Centralized digital identity

creates the ultimate expression of this principle, building

repositories that contain the digital identities of millions of people

and creating irresistible targets for hackers who can achieve maximum

damage with minimal effort.

When these systems are breached, and mathematical certainty tells us

they will be, the damage cascades across entire populations

simultaneously in ways that make individual identity theft look

trivial by comparison, as attackers gain access to comprehensive

personal profiles rather than isolated pieces of information.

Government data hoarding creates what constitutional scholars describe

as “moral hazard”, where the accumulation of power inevitably leads to

abuse as comprehensive surveillance infrastructure becomes a tool for

political control rather than administrative efficiency.

Every database faces constant attacks from sophisticated adversaries

including state-sponsored hackers seeking intelligence, criminal

organizations pursuing profit, and rogue insiders exploiting their

privileged access, making the question not whether these systems will

be compromised but when and how extensively the damage will spread.

Once attackers gain access to centralized repositories of personal

information that governments have so helpfully aggregated into

convenient packages, the breach affects entire populations rather than

individual accounts, creating cascading failures that compromise

everyone simultaneously.

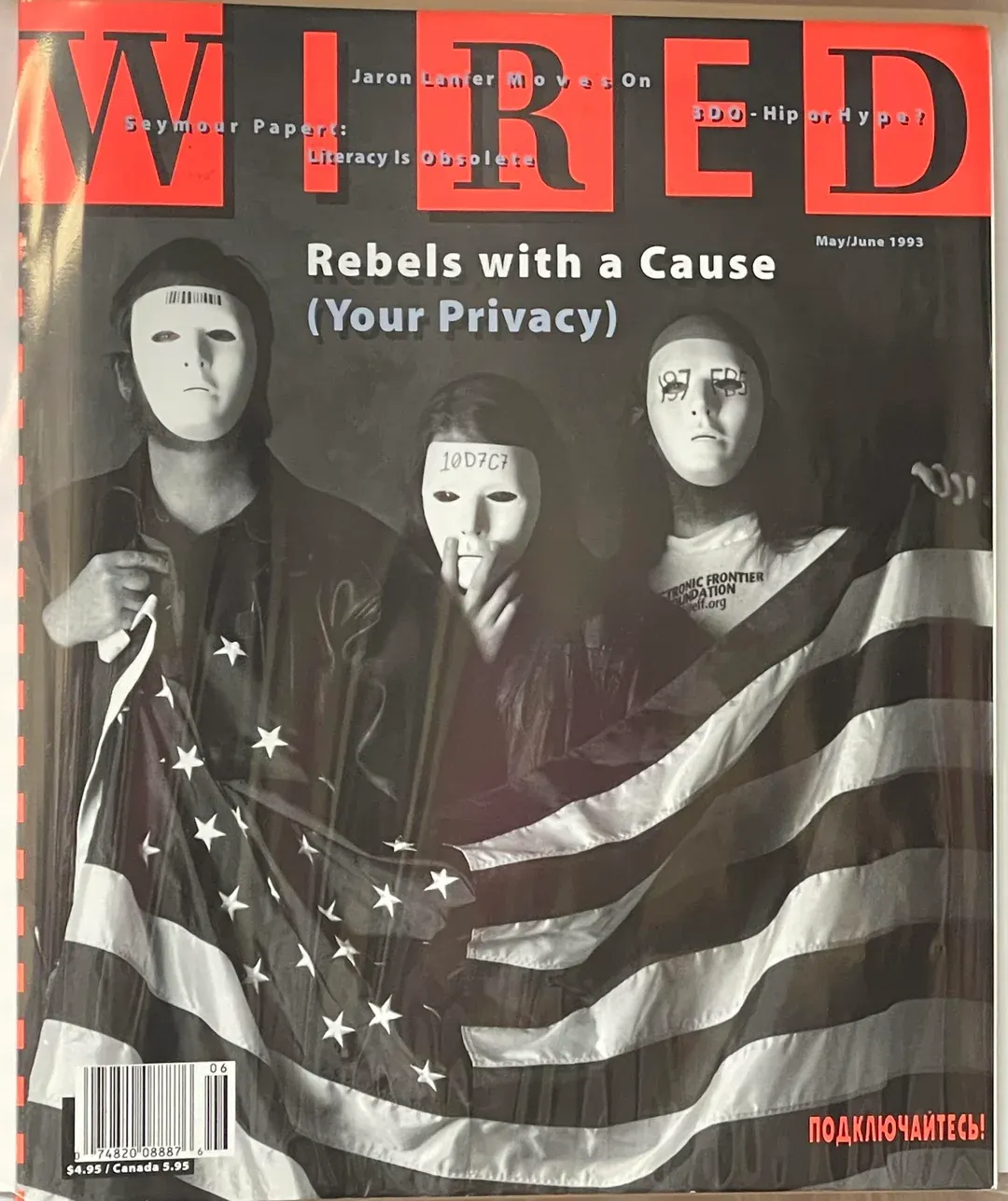

In the 1990s, a group of cryptographers and computer scientists began

exploring radical ideas about digital privacy and individual

sovereignty, envisioning a future where mathematics, rather than law

or trust, would protect individual privacy against government

overreach and corporate surveillance. These “cypherpunks” laid the

foundation for modern blockchain technology and, pivotally for our

current crisis, decentralized identity systems that return control to

individuals rather than concentrating it in government databases.

The fundamental insight is still a powerful one, as the flaws of

centralized digital identity stem from centralized control rather than

digital verification itself, suggesting that self-sovereign identity

systems built on blockchain infrastructure can offer a radically

different approach that preserves verification benefits and eliminates

surveillance risks. Instead of concentrating control in government

databases that become targets for hackers and tools for political

oppression, these systems allow users to maintain their own

cryptographically-secured credentials and decide what information to

share, with whom, and under what circumstances.

As a result, personal data stays distributed across the network as

users maintain granular control over their information, creating

systems where verification becomes possible without the data

collection and surveillance that centralized systems require by

design. The technical foundation relies on proven cryptographic

techniques that enable verification without disclosure, allowing

someone to prove their right to work without revealing immigration

status, nationality, or address and demonstrating eligibility for

services without exposing their complete personal history to

government surveillance databases.

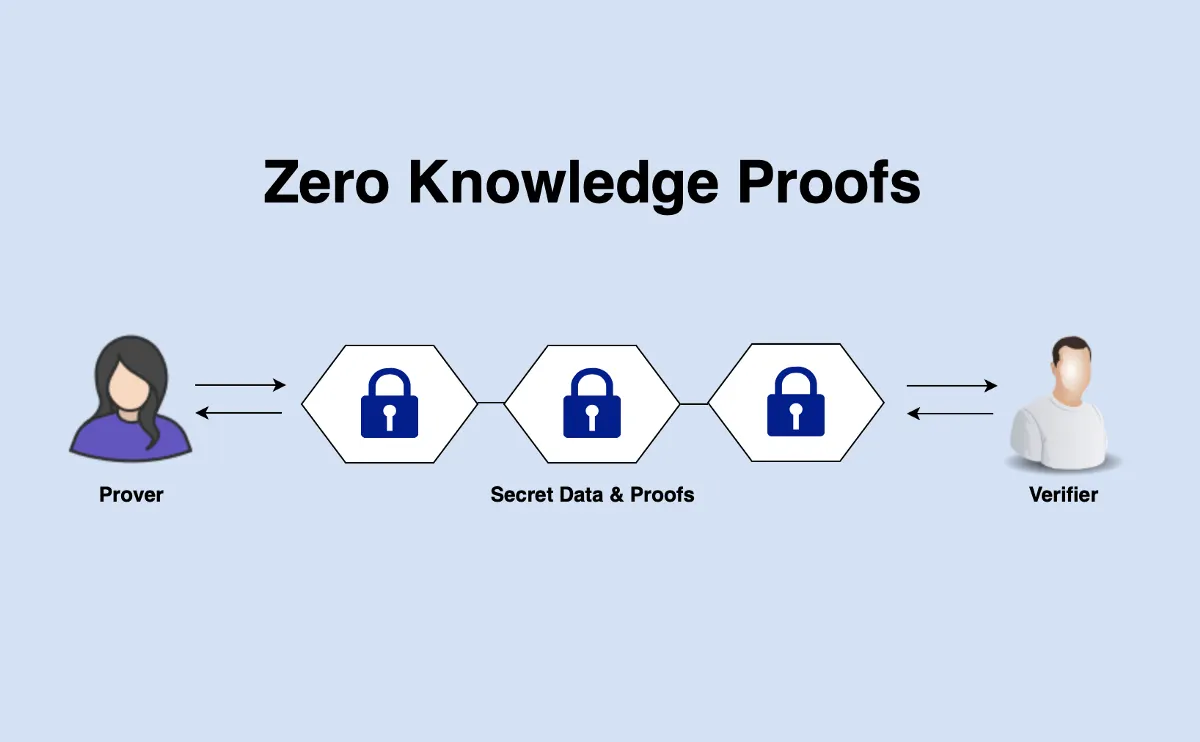

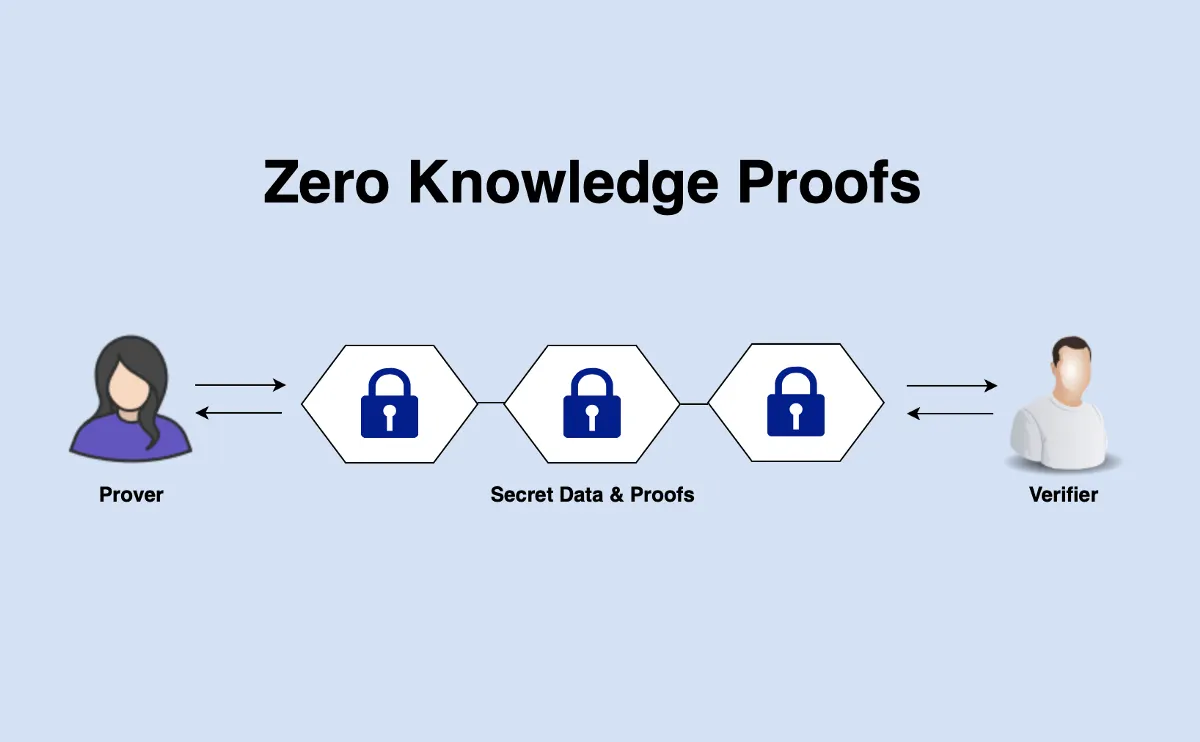

Zero-knowledge proofs make this possible through mathematical

breakthrough, allowing verification of specific claims without

revealing underlying data so a person can prove they’re over 18

without disclosing their exact birthdate, or demonstrate work

authorization without revealing their visa status or nationality.

These aren’t theoretical constructs but proven mathematical tools that

provide stronger security guarantees than centralized systems and

preserve individual privacy and autonomy, creating verification

without surveillance through mathematical certainty rather than

institutional trust.

The cypherpunk vision required more than cryptographic theory,

demanding practical infrastructure that could handle real-world

demands for security, scalability, and user experience as it bridged

the gap between theoretical possibility and practical application.

Each flaw in centralized systems like the UK’s digital ID scheme

points to specific technical requirements that decentralized

alternatives must address, from preventing government surveillance to

eliminating single points of failure to maintaining user autonomy over

personal data.

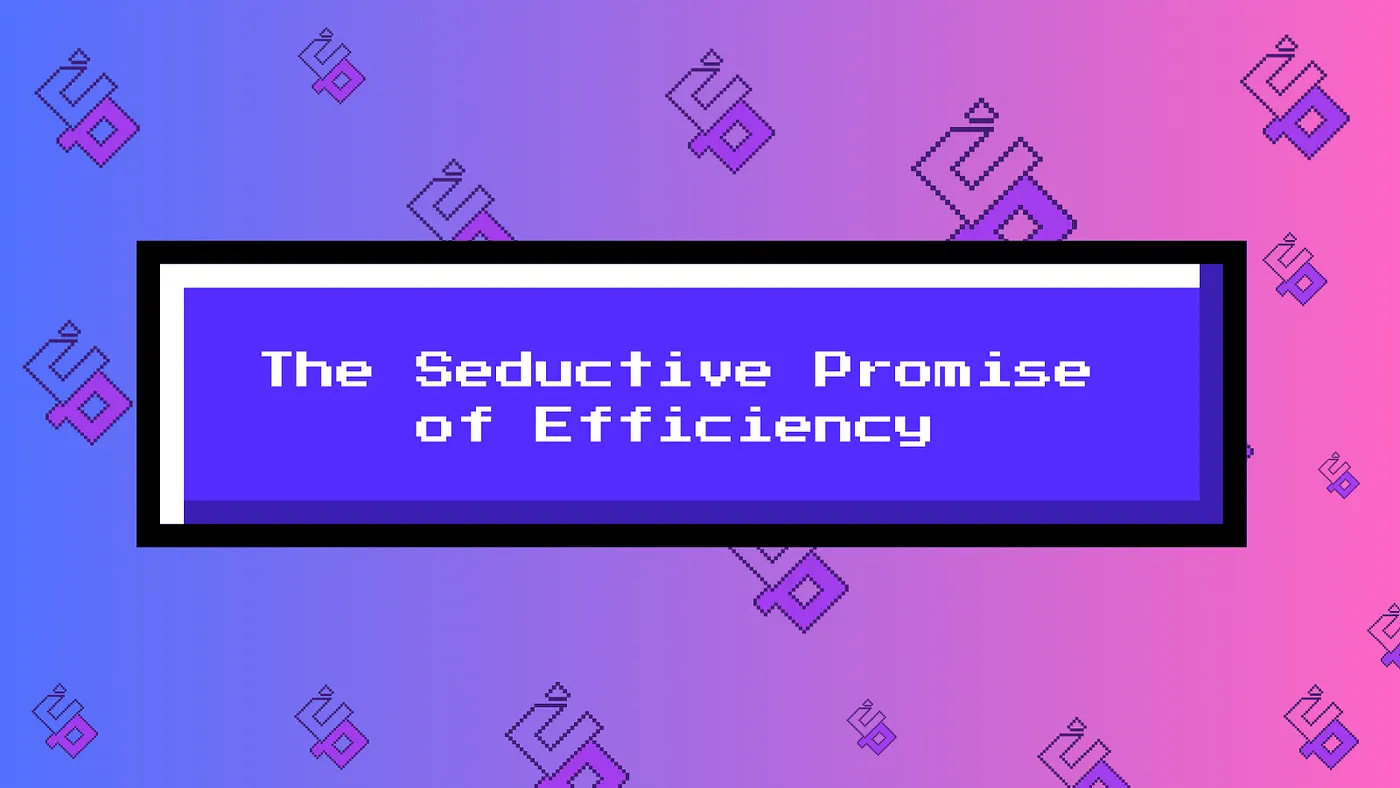

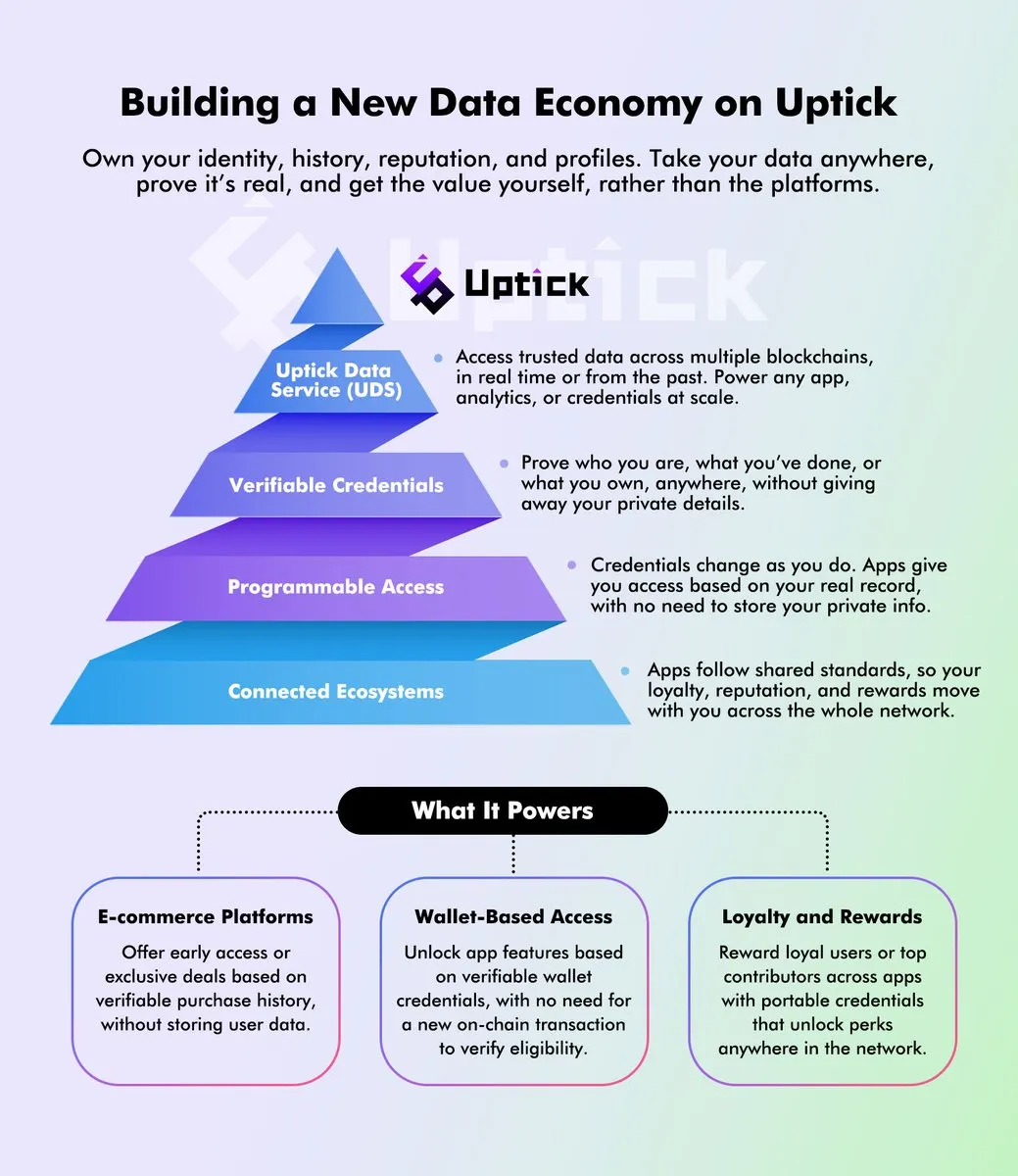

Among decentralized identity implementations, Uptick DID demonstrates

how these principles translate into practical infrastructure that

addresses each failure of centralized systems through proven technical

architecture.

The UK scheme’s fundamental vulnerability lies in centralization,

creating honeypots where attackers can compromise millions of

identities through a single breach. Uptick DID is built on a

distributed architecture using Cosmos-SDK, designed so that users

maintain cryptographic control over their own credentials through

private keys, reducing the concentration of identity data in central

databases.

Government lock-in represents another critical failure, as citizens

trapped in the UK system face no alternatives when their digital

identity privileges get restricted for political reasons or

bureaucratic errors. Uptick DID operates across multiple blockchain

environments through the Uptick Cross-chain Bridge and IBC protocols,

designed to provide consistent identity management across various

ecosystems such as Ethereum, Cosmos, Binance Smart Chain, and Polygon,

so users whose government-issued credentials face restrictions can

still verify their identity and access services through decentralized

networks that transcend political boundaries and cannot be

unilaterally revoked.

The surveillance architecture embedded in centralized digital ID

systems tracks every verification request, building comprehensive

profiles of citizen behavior that enable political control. Uptick DID

addresses this through verifiable credentials that prove identity

claims through zero-knowledge proofs, allowing users to demonstrate

they’re authorized to work without revealing their nationality, visa

status, employer history, or any information beyond the specific

credential being verified, with the architecture designed to enable

peer-to-peer verification where cryptographic signatures confirm

authenticity, reducing reliance on surveillance intermediaries.

Data permanence creates additional risks in centralized systems, where

information collected today persists indefinitely in government

databases and gets repurposed for uses citizens never authorized or

imagined. Uptick’s infrastructure integrates Uptick Storage through

IPFS for decentralized credential storage, creating tamper-proof

records that remain accessible without depending on centralized

servers, though users control what credentials they hold, which

verifiers can access them, and when they choose to revoke access,

providing granular control over digital identity that centralized

systems deny by design.

The UK’s exclusion of citizens lacking smartphones or technical

literacy reveals how centralized digital ID systems create two-tier

citizenship. Uptick addresses this through user-friendly design that

makes decentralized identity accessible without much technical

expertise, combining intuitive interfaces with full cryptographic

protection through cryptographically secured key-pair systems and

zero-knowledge proofs that provide institutional-level security

without institutional surveillance.

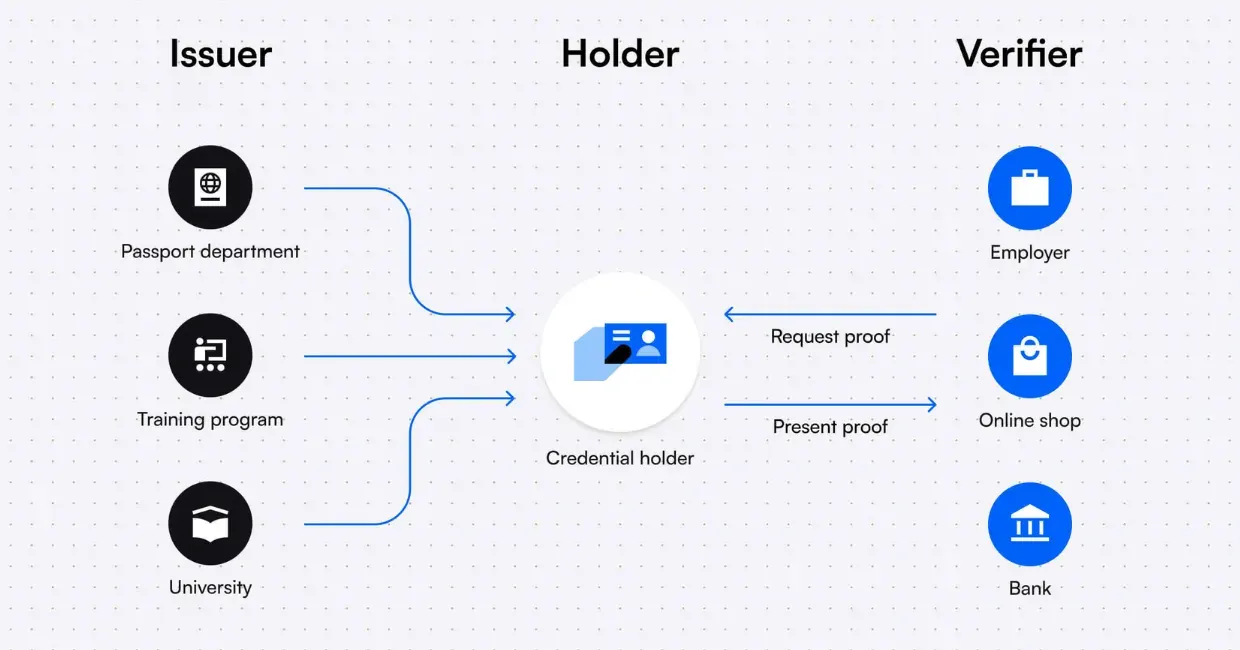

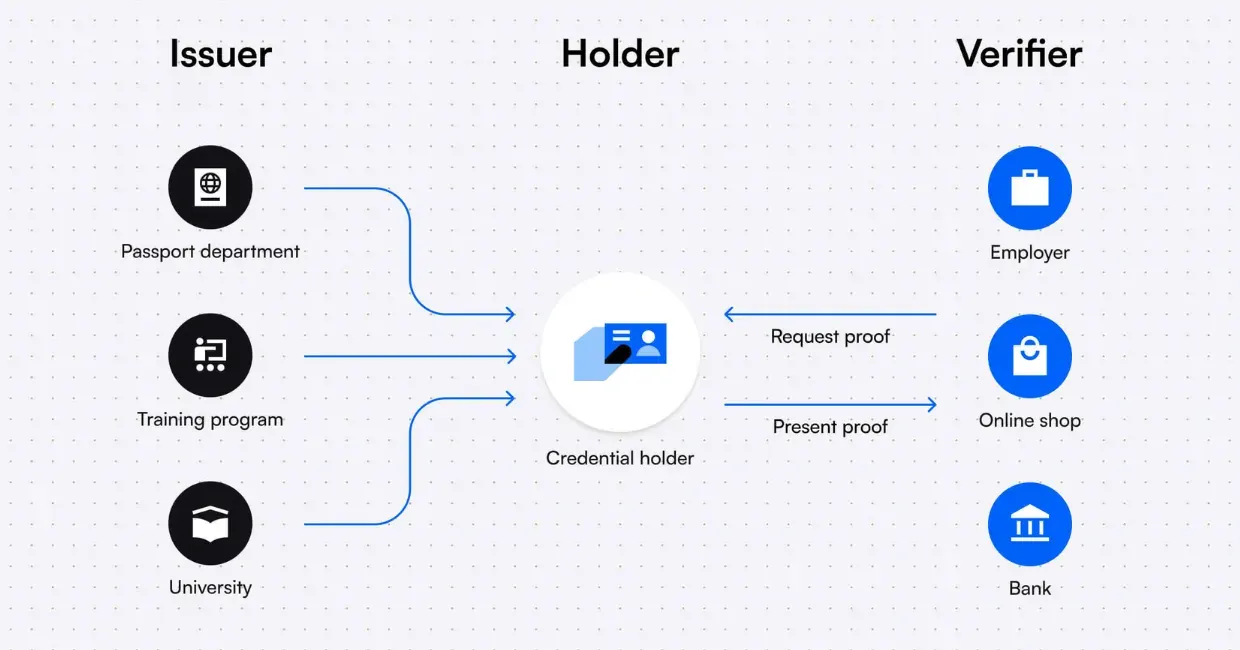

The Vouch platform and Upward Wallet implement this accessible

approach through simplified credential management, where holders keep

full control over their credentials through the issuer-holder-verifier

model, and issuers handle the complexity of credential creation and

verifiers can quickly confirm authenticity.

Perhaps most importantly, centralized digital ID systems offer no

accountability when governments abuse their power, restricting access

arbitrarily or expanding surveillance beyond stated purposes. Uptick’s

decentralized data service is designed to provide transparent tracking

where cryptographic signatures maintain authenticity, recorded

immutably on-chain through auditable processes that replace

institutional promises with mathematical proof, making every action

completely traceable and preventing the invisible abuse that

characterizes centralized surveillance systems.

This problem-solution architecture shows us that decentralized

identity through Uptick DID doesn’t simply replicate centralized

systems on blockchain infrastructure, it fundamentally reimagines how

digital identity can work when designed to serve users rather than

surveilling them. Each technical choice addresses specific failures in

centralized approaches, creating verification without surveillance,

autonomy without exclusion, and security without the concentration of

power that inevitably corrupts.

The economic argument for decentralized identity extends far beyond

cost savings, though those advantages are substantial when considering

the full lifecycle costs and economic effects of different approaches

to digital identity management. The UK’s digital ID system will

require massive government investment in infrastructure, ongoing

maintenance costs, and extensive bureaucratic overhead for

administration and support, with these costs burdening taxpayers

regardless of whether they choose to use the system as it creates

economic incentives for surveillance expansion.

Decentralized systems like Uptick DID distribute costs across the

entire ecosystem and eliminate much of the bureaucratic overhead,

allowing peer-to-peer verification through smart contracts that

reduces administrative costs and improves security and privacy through

mathematical rather than institutional guarantees. Despite the fact

that decentralized systems require initial investment in user

education and infrastructure setup, the elimination of ongoing

bureaucratic overhead and centralized maintenance costs creates

long-term economic advantages that compound as network effects reduce

per-user costs.

Use cases like credential verification could be streamlined through

Uptick’s combination of decentralized identity and smart contract

automation, with verifiable credentials enabling users to prove their

identity, qualifications, or attributes without relying on centralized

services, creating efficiency gains that extend beyond direct cost

savings to include reduced friction in economic transactions.

These economic advantages create positive feedback loops that

encourage innovation and adoption, with network effects increasing

value for all participants as more organizations and individuals join

Uptick’s decentralized identity ecosystem and continuing to reduce

costs through improved efficiency and automation. The result is a

virtuous cycle where better technology creates better economics, which

drives broader adoption and further technological improvement, making

decentralized systems increasingly attractive compared to centralized

alternatives that burden users with surveillance costs they never

chose to bear as benefits concentrate among government agencies and

their contractors.

Perhaps the most radical aspect of decentralized identity systems lies

in their governance models, which replace political control with

mathematical certainty and community consensus as they eliminate the

corruption and bias that characterize centralized systems. Uptick’s

implementation includes DAO functionality through its Social DAO

infrastructure that allows communities to establish and maintain

governance standards and community decision-making processes,

providing governance that can adapt to different community needs as it

maintains security and reliability benefits through transparent,

auditable processes recorded immutably on-chain.

DAO governance provides transparency and accountability that is

typically absent from government systems, with all governance

decisions recorded on-chain and auditable by any community member as

it maintains consistent and fair application of identity verification

standards without the potential for political manipulation or

discriminatory treatment that plagues centralized systems. Even though

DAO governance faces coordination challenges inherent to decentralized

decision-making, the transparency and immutability of on-chain

processes provide accountability guarantees that centralized political

systems simply cannot match, creating mathematical rather than

institutional constraints on power.

The decentralized governance model allows innovation and

experimentation in identity verification approaches, letting different

communities test various methods as successful innovations spread

through voluntary adoption rather than top-down mandates imposed by

political authorities. This creates a marketplace of governance models

where, for the most part, the best approaches succeed through merit

rather than political power, preventing the regulatory capture and

bureaucratic ossification that characterize centralized systems as it

allows communities to collectively own and govern their identity

verification systems.

This kind of ownership creates stakeholder alignment that encourages

long-term sustainability rather than the political short-termism that

drives government policy, resulting in governance systems that serve

community needs rather than political ambitions.

The UK’s digital ID scheme forms part of a global trend toward

increased government surveillance and control through digital identity

systems, with similar programs being implemented worldwide as they’re

justified through familiar rhetoric about security, efficiency, and

fraud prevention that obscures their true purpose as population

monitoring infrastructure. This moment will define the evolution of

digital society, determining whether we accept surveillance as the

price of convenience or build alternatives that preserve both security

and freedom through technological innovation rather than political

capitulation.

Decentralized identity through solutions like Uptick DID offers a

pathway for resisting this trend toward digital authoritarianism as it

preserves the legitimate benefits that digital identity can provide,

showing the world that secure, efficient identity verification is

possible without surrendering control to centralized authorities who

inevitably abuse their power. The global nature of the blockchain

means decentralized identity systems can operate across national

boundaries through Uptick’s cross-chain protocols, providing

individuals with identity verification capabilities even when home

governments implement restrictive digital ID schemes as it creates

international interoperability that transcends political control.

As more individuals and organizations adopt Uptick’s decentralized

identity infrastructure, they create pressure for governments to

abandon authoritarian digital ID schemes in favor of

privacy-respecting alternatives, with the economic and efficiency

advantages of decentralized systems providing compelling reasons for

businesses and institutions to support DID adoption even in the face

of government resistance. Though governments may resist through

regulation or mandates favoring centralized systems, the economic and

security advantages create incentives that can overcome political

resistance as businesses and citizens recognize the costs of exclusion

from decentralized ecosystems that operate across jurisdictions.

Essentially, network effects create powerful incentives for adoption

that can overcome political resistance, as the benefits of

participation increase with network size and the costs of exclusion

from decentralized identity ecosystems like Uptick become increasingly

apparent to organizations and individuals alike.

Britain stands where Jeremy Bentham’s England once did, at the

threshold of a new form of social control disguised as progress, with

the government’s digital ID scheme creating comprehensive surveillance

infrastructure that concentrates unprecedented power in centralized

authorities as it creates massive vulnerabilities for citizen privacy

and autonomy. The alternative path leads toward decentralized systems

like Uptick DID that provide verification benefits without

authoritarian implications, using mathematical guarantees rather than

political promises to protect individual freedom as they preserve the

legitimate benefits of digital identity verification.

The technology exists today to build decentralized identity systems

that are more secure, more private, and more efficient than

centralized alternatives, with Uptick’s DID infrastructure

demonstrating that these systems can handle real-world demands as they

preserve individual sovereignty and democratic values through

practical implementation rather than theoretical possibility. The

infrastructure for digital freedom exists as the economic incentives

favor privacy-respecting solutions over surveillance systems, leaving

only the political will to choose decentralized identity over

centralized control before government digital ID schemes become

entrenched and impossible to reverse.

What remains is recognizing that the UK’s experience serves as a

warning about how quickly democratic societies can adopt authoritarian

technologies when citizens accept promises about security and

convenience without examining underlying power structures or

considering alternatives that preserve both safety and freedom. The

future of digital identity depends on choices made today, determining

whether we accept the UK government’s vision of mandatory digital ID

schemes that concentrate power in centralized authorities, or build

decentralized alternatives through platforms like Uptick Network that

preserve individual autonomy and privacy through technological

innovation rather than political submission.

The question isn’t whether we have the technology to make

decentralized identity a reality, it’s whether we have the wisdom and

courage to choose it before the digital panopticon becomes as

inescapable as Bentham’s physical version was intended to be.

In Bentham’s time, the panopticon remained a theoretical construct

that never achieved full implementation, but today’s digital

panopticon faces no such limitations, making our choice both more

urgent and more consequential than any previous generation has faced

in the struggle between freedom and control.